Dungeness Crabs and Crab Fishing

Dungeness Crabs and Crab Fishing

Dungeness crab (Metacarinus magister), named after a small town and the shallow bay inside of Dungeness Spit on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, is the culinary jewel of Netarts Bay, a prime destination for crabbers. Thousands visit the bay each year, launching their boats, setting their traps and crab rings, or casting baited snares into the mouth of the bay from the beach in front of Happy Camp. Crabbing is open all months of the year, though some crabs caught during the summer and early fall may have recently molted and have soft shells and little meat.

We would like to tell you about some of the interesting biology of the Dungeness crab, so when, for example, you clean a crab you can recognize some of its parts, or when you catch soft-shell crabs you will know why they are soft-shelled and have little meat.

Crab Anatomy.

The Dungeness crab is a member of the ten-footed crustaceans, the decapods. Its two forward legs, the pincers, technically called chelipeds, are used for both defense and feeding. The remaining eight legs are for walking.

The Dungeness crab is a member of the ten-footed crustaceans, the decapods. Its two forward legs, the pincers, technically called chelipeds, are used for both defense and feeding. The remaining eight legs are for walking.

The first thing a crabber should know is how to tell a male from a female, since it is currently unlawful to keep females. Look at the underside of the crab . If the abdomen, the flap of shell that folds under from the rear end of the crab, is wide and rounded, the crab is a female. If the abdomen is narrow, it is a male.

Still looking at the crab from the underside, but forward between the chelipeds, you can see the overlapping parts of the mouth that are used for grasping and biting off chunks food. Turn the crab over. The large back is called the carapace. On the anterior or front part of the carapace you can find the stalked compound eyes and the antennae. The antennae are chemorec eptors. They allow the crab to taste and smell, to find food and mates.

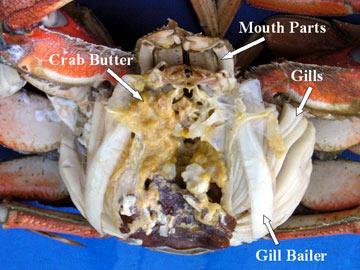

When you pull the back off a boiled crab, you will see a number of anatomical structures and some mushy yellowish stuff, some of which is clinging to the inside of the shell. You may notice first the new cuticle that is forming for the next molt. It has the appearance of shell, but is soft and fleshy. The yellow mush, sometimes called crab butter, is the hepatopancreas, the digestive gland, equivalent to our liver and pancreas. It is used for energy storage and the secretion of digestive enzymes. Some people consider this a delicacy, but if it is from crabs taken from polluted areas, it may contain contaminants such as PCBs, heavy metals, or in our area the neurotoxin that causes Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning (ASP). Chemical pollutants are not a problem in pristine Netarts Bay, but ASP can be.

The long, triangular structures on each side of the center of the body are the gills. Each gill consists of a stack of lamellae, thin plates with a single layer of cells surrounding a blood sinus, each lamella resembling a miniature hollow pita bread. The lamellae are connected to blood vessels that travel the length of the gill. The gills lie in a pair of cavities called the branchial chambers. Water is moved through each chamber by a fringed, paddle-like appendage -the gill bailer, technically called the scaphognathite. Its ore-like motion moves water backward along the bottom side of the chamber, up along the gills and between the lamellae where oxygen is extracted, then forward where it is expelled out the mouth region. Other fringed, paddle appendages in the branchial chamber clean the gills.

Centered in the crab between the two sets of gills is the heart, a rectangular sack connected to arteries that feed blood to capillaries and tissues. The blood of the Dungeness crab is colored blue due to its copper-based respiratory pigment, hemocyanin. If you see a bluish colored liquid in the bottom of a bucket of live crabs, that is crab blood. Just forward of the heart is part of the stomach called the cardiac chamber, which contains the gastric mill, teeth that grind food. Dungeness crabs typically eat clams, snails, crustaceans (including baby Dungeness crabs), marine worms and small fish.

Molting.

Molting.

The exoskeleton, a characteristic of crustaceans and all arthropods, is comprised of the cuticle, a complex of proteins and a polysaccharide called chitin. In the Dungeness crab, it surrounds the outside of the animal, and also some internal structures such as the gills. It also lines the gut, where it is thin and porous. Parts of the exoskeleton are calcified and ridged and form the shell, giving the crab a suit of armor that is hinged at the joints. The shell can not expand as the crab grows, so the crab must periodically shed its old shell to allow for a new, larger one. This is the process of molting. Secretion of hormones starts the molt cycle. A new cuticle forms, separates from the old cuticle, and some calcium is reclaimed from the old shell. The crab quits feeding before molting and does not resume eating until well after. It relies on energy reserves stored mainly in the hepatopancreas. When the exoskeleton is shed during the molt, a fracture opens along the back of the crab, just below the carapace along what is called the molt line, and the crab backs out of its old cuticle - shell, gills, gut lining and all. The new cuticle, soft and wrinkled, fills with water and swells up to thirty percent, adding up to an inch to the width of the crab. The crab at this time is extremely vulnerable to attack and predation. It hides buried in the sand several days until the shell starts to harden. It then begins to feed to restore its energy reserves, fill out its muscles, and completely harden its shell, which may take up three months. It is during this recovery period that we find soft crabs with poor quality meat.

Young crabs may molt several times a year, but by the time they reach about four inches in width, the frequency is reduced to about once a year. Females molt before the males so they can mate (see below). Males usually molt during summer and early fall, but this can vary. Dungeness crabs will live to about eight years.

Mating.

Dungeness crabs mate during the spring and early summer. This account of crab sex is taken from the book, "Between Pacific Tides" by Ricketts, Calvin, Hedgpeth, and Phillips and is based on research originally doneby the Oregon Fish Commission. Love making in the Dungeness crab takes place soon after the female molts and her shell is soft, but before the male molts and while his shell is hard. First the male embraces the female firmly, belly-to-belly, holding her this way for several days, stroking her gently with his chelipeds. When she is ready to molt, she signals the male by nibbling at his eyestalks. He loosens his grip, allows her to turn over, and she molts while still confined by his legs. After she molts, the male shoves away her cast off exoskeleton. There is a short waiting period, about an hour, before actual mating, possibly to allow some hardening of the carapace. When the moment arrives, she turns back over, again belly-to-belly, lifts her abdominal flap to receive the male's gonopods (the two appendages you see under his abdomen when you clean a crab and pictured at right) into her spermathecae, the receptacles in the female that hold the spermatophores. Spermatophores are packages of sperm delivered by the male. The sperm in these packages are viable for months, even through a second molting of the female. Males are not monogamous. They may mate with several females in a season. When the eggs in the female, which may number in the millions, mature, they are extruded and held under the abdomen where they are fertilized. The mother carries the eggs until they hatch.

The eggs hatch into free-swimming prezoeae larvae, then progress through five zoeal stages, formidable looking creatures when viewed through a microscope with big eyes and long rostral and dorsal spines. The zoeae metamorphose into megalops larvae that resemble elongated miniature crabs with a long tail. The megalops finally molt into juvenile crabs.

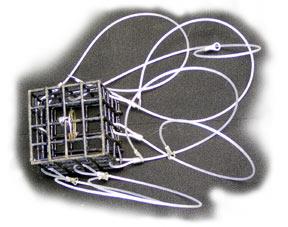

Crabbing with crab rings

Catching Dungeness Crabs. Crabbing is good many places in Netarts Bay, not only in the deeper channels, but even in the upper bay, in the eelgrass beds where they like to hide. There are several ways to catch crabs. Some require a boat; some can be done from shore or by wading. A "crab pot", used from a boat, is a baited trap that allows crabs to enter but not exit. It is attached to a rope and a buoy that floats on the surface. Pots can be left in the water for hours, even overnight, after which the crabs are collected. They come in several configurations, round or box-like collapsibles. Crab rings (slip rings or open rings) are also buoyed and used from a boat. The rings make a collapsible net, which is baited and left to sit on the bottom. After ten or more minutes, when the crabs are attracted to the bait, the boat is maneuvered over the rings. The rings are then pulled in, gently at first to get the slack out of the rope and not scare away the crabs, then rapidly (if using the open rings) to get the crabs into the boat before they escape. Bait for traps and rings can include fish carcasses, clams, chicken, turkey, and mink. The ever-present harbor seals in Netarts Bay may rob rings of fish and clams, but they avoid turkey, chicken, and mink.

You can catch crabs from shore using a spinning rod by casting out a crab snare or a folding trap. This is a popular activity on the beach at Happy Camp during low tide, as pictured in the header photo at the top of this page. You can also wade in eelgrass shallows of the upper bay at low tide and capture crabs with a net or a pitchfork with blunted tines.

Crab snare

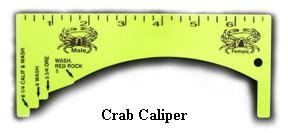

Where to measure a crab

A license is required in Oregon for all shellfish, including crabs. Three traps, rings, or lines are allowed per person. The current catch limit is 12 male crabs per day with no more than two limits in possession. You are not allowed to keep females. The minimum size is 5-3/4 inches as measured by a caliper. Size is measured across the back, immediately in front of, but not including, the points as shown in the figure. Check for additional regulations in the Oregon Sport Fishing Regulations published yearly by Oregon Fish and Wildlife

Red Rock Crabs. Another tasty, but smaller, crab related to the Dungeness is the red rock crab, Cancer productus, which can be identified by its brick red shell. It prefers a rocky habitat, but can be caught on soft bottoms as well. The current catch limit is 24 crabs of any size or sex.

Cooking crabs.

Crabs are usually boiled or steamed for about twenty minutes. Many people prefer seawater or one-to-one seawater to freshwater for boiling. Alternatively, you may add salt to tapwater. If you find plunging a live crab into boiling water distasteful, you can kill it first by hitting it solidly on the underside, just above the point of the abdomen, with a blunt object. This is the location of the thoracic ganglion, a nerve center, and it is equivalent to whacking the crab on the head, if it had a head. You can even clean your crab before cooking. Clean crabs by separating the carapace from the body by pulling it upward from the backside. Remove the viscera, gills, gill bailers and cleaners, the mouth parts, and the abdomen. Save the crab butter if you like, but again we recommend not eating it. Rinse the remaining crab with a spray of cold water until it's clean.

Crabs are usually boiled or steamed for about twenty minutes. Many people prefer seawater or one-to-one seawater to freshwater for boiling. Alternatively, you may add salt to tapwater. If you find plunging a live crab into boiling water distasteful, you can kill it first by hitting it solidly on the underside, just above the point of the abdomen, with a blunt object. This is the location of the thoracic ganglion, a nerve center, and it is equivalent to whacking the crab on the head, if it had a head. You can even clean your crab before cooking. Clean crabs by separating the carapace from the body by pulling it upward from the backside. Remove the viscera, gills, gill bailers and cleaners, the mouth parts, and the abdomen. Save the crab butter if you like, but again we recommend not eating it. Rinse the remaining crab with a spray of cold water until it's clean.

A good recipe book is "Crab" by Cynthia Nims (2002), Northwest Homegrown Cookbook Series, West Winds Press, Portland, Oregon.

Text and photographs by Jim Young

Text and photographs by Jim Young